The Basso Continuo

Basso Continuo, in music, a system of partially improvised accompaniment played on a bass line, usually on a keyboard instrument. The use of basso continuo was customary during the 17th and 18th centuries, when only the bass line was written out, or “thorough” (archaic spelling of “through”), giving considerable leeway to the keyboard player, usually an organist or harpsichordist, in the realization of the harmonic implications of the bass in relation to the treble part or parts. A low melody instrument, such as a viola da gamba, cello, or bassoon, usually served to reinforce the bass line, and the keyboard player received additional guidance in most instances from figures placed above the bass notes, a kind of musical shorthand indicating the intervallic constitution of the chords in question.

Basso continuo composition was a logical outgrowth of the monodic revolution (c. 1600), which declared the supremacy of the treble in opposition to the textural homogeneity of Renaissance polyphony. The harmonic substance of multivoiced music was now literally contracted into an instrumentalist’s two hands; the immediate repercussions for both sacred and secular music prompted Agostino Agazzari as early as 1607 to publish a manual of instructions, Del sonare sopra ’l basso (“On Playing upon the Thoroughbass”).

According to J.F. Daube’s General-Bass (1756), the style of improvised accompaniment was brought to its height by J.S. Bach:

“He knew how to introduce a point of imitation so ingeniously in either right or left hand and how to bring in so unexpected a counter-theme, that the listener would have sworn that it had all been composed in that form with the most careful preparation.”

Basso continuo was thus not merely a convenient shorthand; it gave zest to the accompaniment by inviting the performer to draw on his capacity for spontaneous improvisation.

Basso continuo realization can vary from simple harmonization to extensive explorations of harmony and counterpoint. A “full accompaniment” may require as many notes as the fingers can accommodate, and in such cases the rules forbidding consecutive fifths and the like are waived, except as they apply to the two outside (bottom and top) parts.

Figured Bass

Lesson excerpt from Fundamentals, Function, and Form by Andre Mount

Figured bass comes from a Baroque compositional practice in which composers used a numerical shorthand to provide an accompanist with a harmonic blueprint. This consisted of a notated bass line coupled with a series of Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, etc.) and various other symbols.

Of the three chord members, the root of a triad is considered to be the strongest and most essential. In terms of voicing, the bass note—the lowest sounding note—is often heard as supporting the notes that appear above it. When these two things align—that is, when the root of a triad appears in the bass—we tend to hear the chord as being very grounded: the most stable chord member is in the most stable part of the chord. Of course, the third and fifth may appear in the bass as well, in which cases the chord will sound comparatively less stable.

The numerals and symbols above or below the notes on the lower staff indicated intervals to be played above the bass. The placement of the actual pitches (register, doublings, etc.) was left to the accompanist. In this way, the composer would be able to quickly specify harmonic progressions, though not the chord voicings or, for the most part, the voice-leading from one chord to the next.

Figured bass is useful in two ways:

for indicating chord inversions and

for representing intervals and melodic motion above a bass line.

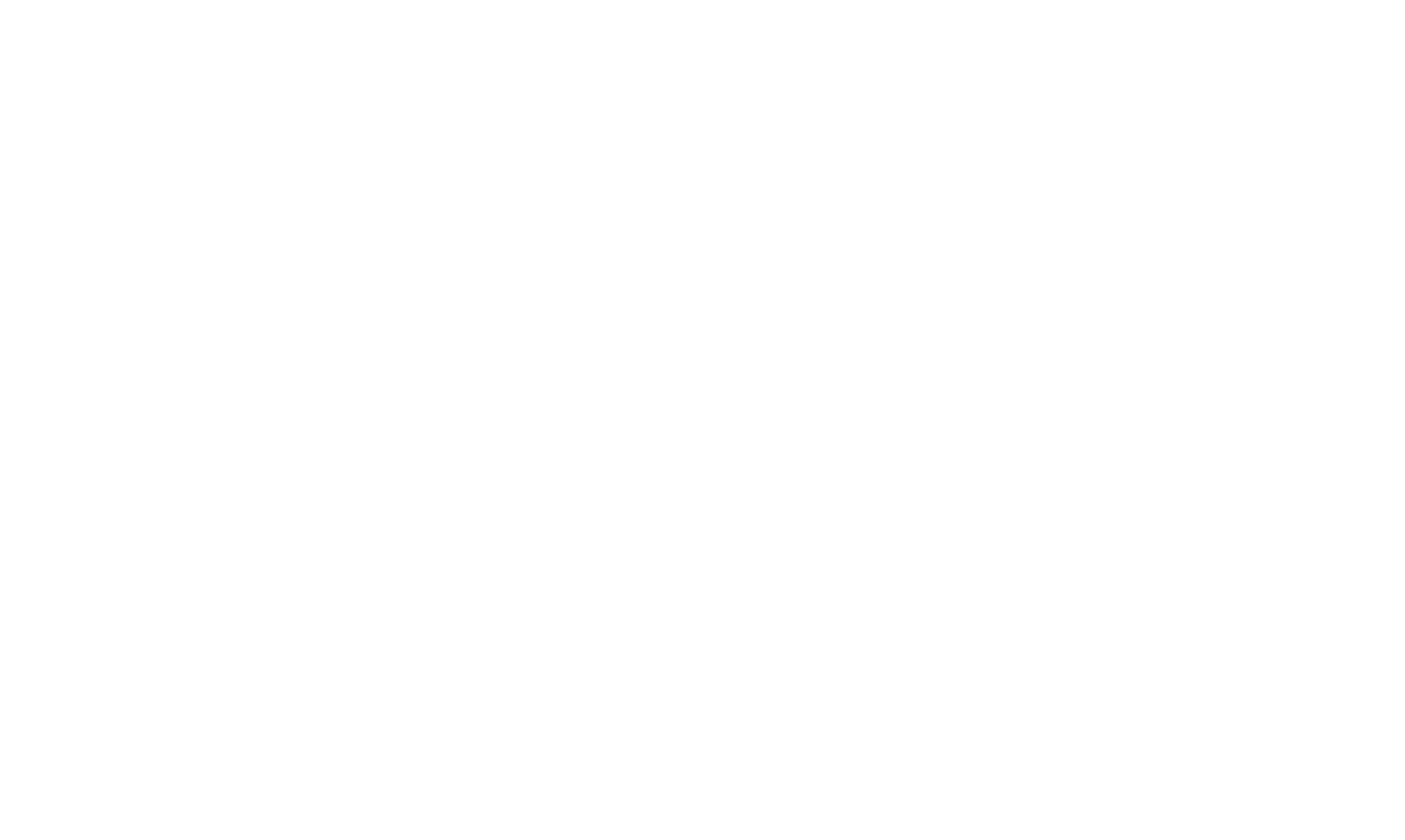

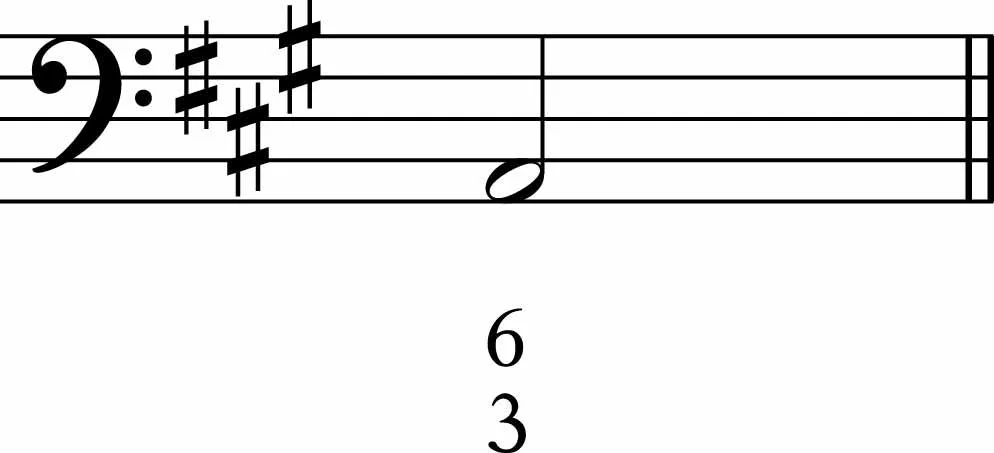

As explained above, the Arabic numerals indicate intervals above the bass. In other words, the 6 and the 3 specify that a sixth and a third must occur somewhere above the A. The quality of each interval (major, minor, etc.) is determined by the key signature unless otherwise specified (more on this below). In this case, a third above the A in the bass would be C# and a sixth above the bass would be an F#, as dictated by the A-major key signature. The following example shows the complete chord, an F#-minor triad in first inversion:

The figures specify the intervals to be played above the bass in a generic way. They do not specify the register of pitches forming those intervals. In other words, any interval indicated by the bass figures may be compounded by one or more octaves.

Let’s Expand on this example again!

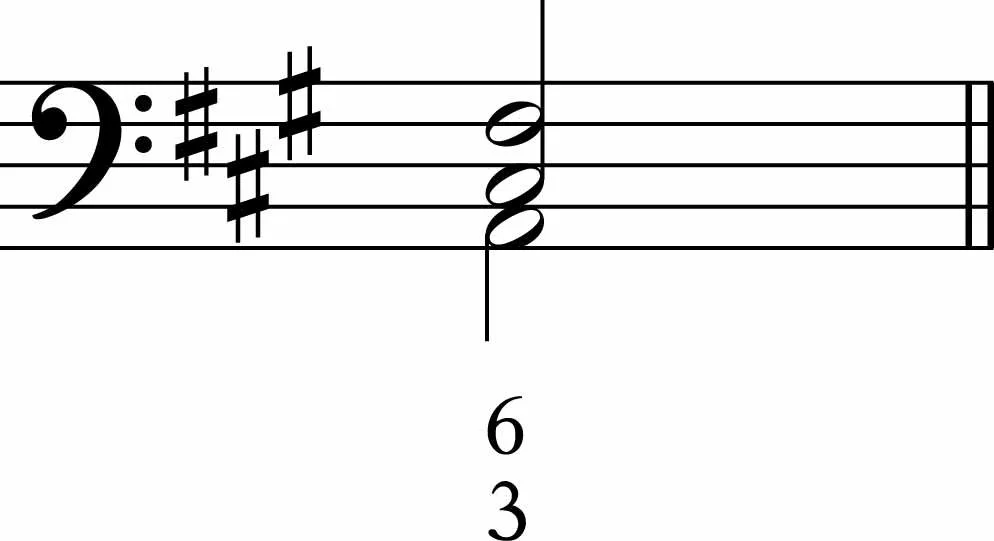

The figures specify the intervals to be played above the bass in a generic way. They do not specify the register of pitches forming those intervals. In other words, any interval indicated by the bass figures may be compounded by one or more octaves. Take another look at the example above. The C# was placed two steps above the bass note A. It would have been equally valid to place the C# on the first ledger line above the bass staff—or in any other octave, provided the note lies somewhere above the bass:

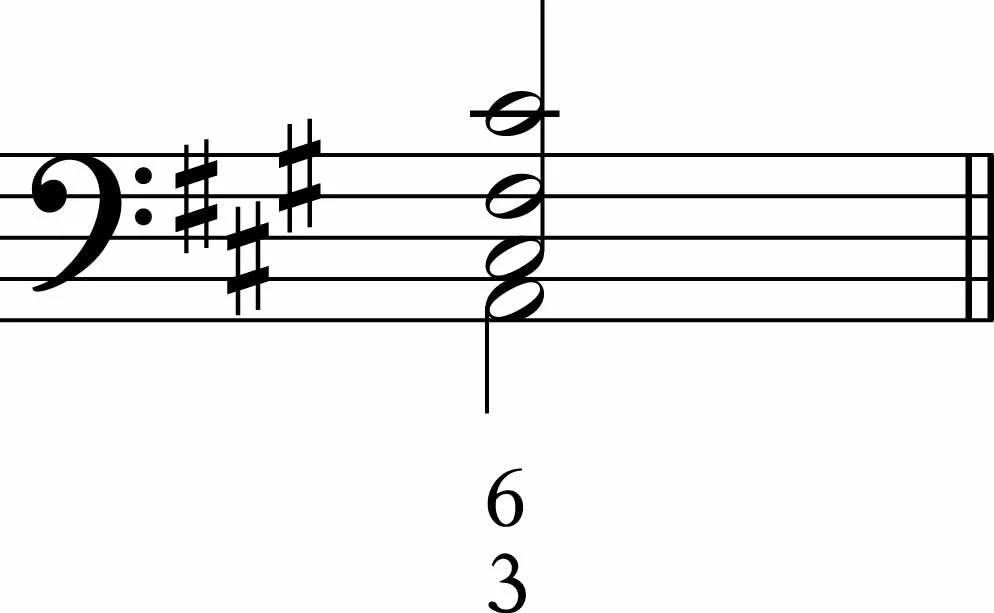

As we will see later on, the decision to realize a bass figure as a simple or compound interval will depend on the musical context. Furthermore, bass figures do not specify anything about doublings—two or more members of the same pitch class appearing in different registers. It would therefore be equally valid to include both the C# just above the bass and the C# an octave higher:

The first voicing has wider spacing and doubles the bass two octaves above in the alto. The second voicing doubles the sixth and has the voices more tightly arranged. Despite these somewhat superficial differences, however, all of the examples above show the same chord: an F#-minor triad in first inversion (a i chord in F#-minor or a vi chord in A major).

Quick and intelligent use of figured bass writing requires a singer to have strong control of their triads and inversions. So this is a good time to break out those Scale Pages!